A quick announcement before we begin; the new anthology

Shadows of a Fading World from Long Count Press went live today. This collection contains tales of dying worlds, and among them is my story "Paths of Iron and Blood". If you're interested, check it out

here on Amazon.

Now then, where was I? Oh yes...

The Mary Sue

Mary Sues; even if you don't know the name, you know these characters. They're the youngest, the smartest, the prettiest, and they just have the cutest eyes and the most tragic back stories. Everyone loves them, and those who don't hate them only out of jealousy and spite.

These characters are, no exaggeration intended, the things editors see in their nightmares.

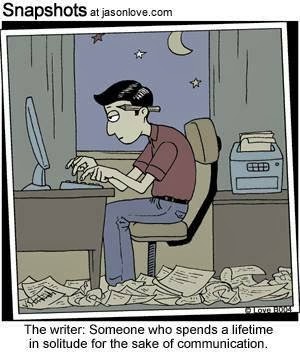

|

| And this. Editors have nightmares about this. |

Some authors strain with every fiber of their being to avoid creating these types of characters. Some of us are in denial about the problems with our own, imaginary children and won't see them until beta readers set our manuscripts on fire on our front lawns in protest. To avoid this, there are some easy ways to make sure all your characters, not just your leads, avoid becoming one of these shallow gateways to wish fulfillment.

Step One: Take the Test

There are dozens of tests out on the Internet which can give you feedback on how much of a Mary Sue your character is or isn't. One of the most reliable tests I've come across is the Universal Mary Sue Litmus Test, which can be found

here. Running your character through this test should always be your first step, even if you're positive he or she is clean.

Step Two: Scrub Off Some of The Special

Your characters are not beautiful, unique snowflakes; they're people. Every person, and every character, has a list of abilities, skills, and a history that's led them to become who they are in this moment. Even the waiter whose name we never learn on page 75. However, if your character is a little

too remarkable for the world you've created, a lot of readers are going to get turned off right quick.

|

| Guess which section is responsible for this? |

Here's a little history lesson for you. The Mary Sue, according to the eminently reliable source of

a Wikipedia article, is the direct result of Star Trek fan fiction. The actual character by the name of Mary Sue was created and published in the fanzine

Menagerie #2 in a 1973 story titled "A Trekkie's Tale". This story set out to deliberately show how ridiculous a fifteen-and-a-half-year-old lieutenant, the youngest and brightest ever to graduate from the academy and to be given a field commission, was. This story was in response to a huge number of tales with similar self-insert characters who, despite their youth, were precocious enough to save the day in addition to getting in bed with canonical, adult-aged characters.

Firstly, I'm sure there's a regulation somewhere against that kind of thing in any navy. Second, no.

So, if your character scored too high on the Mary Sue Litmus Test (again, you can and should take it

here), then you need to look at what makes him or her too special. Is the character too young to be established in a certain field? Does the character have impossible-colored hair, eyes, or other features which mark him or her out as obviously special and different? Has the character mastered some skill or discipline uncommon to the world, such as being a disciple of an ancient martial art known to a chosen few or being one of the most naturally talented spellcasters in existence?

Whatever it is, ask yourself if it's necessary to the character. For instance, does your lead

have to be an ex-special forces soldier, or would simply being someone who served in the military do? Must this character have pink, blue, or fuchsia hair, or is it a minor, cosmetic thing that can be done away with without altering the story?

Step Three: Make Your Character Work For It

When you watch a lead guitarist shred on stage, an expert marksman put two rounds right next to each other at a half a mile in a high wind, or hear about someone who climbs buildings like a human fly, you see something amazing. What you don't see is the countless hours of practice, training, study, blood, sweat, and shouted swear words that went into that final product. You need to make the reader aware of how your character became what he or she is.

|

| All right wuss, if you make good time I'll take the razor blades out of the grips. |

That said, do not, I repeat,

do not just list a character's bona fides up front; instead, show them gradually to the reader. I did a post about this

here too, but examples always work best. So, say you have a character who is the most talented sorceress the realm has ever seen. Magic comes naturally to her, and she's able to weave spells that should be years beyond her with nary a thought.

That's boring. Even if a character is born with talent, that talent has to be beaten, hammered, and refined into real world skill. Anything worth having takes work.

Take the same character and the same power set, but this time show how hard she worked to be where she is. Have her use jargon unique to magic, and show how intimately she understands the process of manipulating the power. If she does it naturally, treat her more like an athlete than an academic. Point is, she's had to refine what she does to be that good. More importantly though, you need to show us how attaining that level of mastery has marked her worldview and her skill set. Perhaps she can weave fire with a single breath, but does she know how to dance? Maybe she can call lightning from a cloudless sky, but does she understand how to relate to other people? Especially people who don't see the world in terms of elements and power, but rather in terms of growing seasons and harvests?

By dedicating a character so fully to achieving mastery of one area, she has had to sacrifice learning in other areas. She may find it hard to understand the viewpoints of those who are not as learned as she is, or who can't perform even simple magic. You see this in everyday professions as well; what people do shapes their perceptions of the world. Police officers, even when they're off duty, pay attention to faces and movements just in case something goes wrong in their presence. Medical professionals may find it impossible not to see people as collections of tissues and bones, or symptoms and issues, even when they're at home or at a party. By showing us where a character lacks, we find it easier to accept where he or she succeeds.

Step Four: Take the Test Again

I already gave you the link twice. You're not getting it again.

At The End of The Day...

It's important to remember that not every character who looks like a Mary Sue really is one. Run characters like Batman, Morpheus, Doctor Who, and a dozen others through the test, and they'll be rated as irredeemable Mary Sue characters. People love them despite that rating, and they're all million-dollar institutions.

Why, you might ask? Is it because deep down people really love over-powered escapist fantasy? No. The reason any characters with ridiculous powers and trope-laden backgrounds are popular is because they're compelling. They have depth, emotion, and they suck the readers in. It's also very clear that these characters are their own people; they aren't just super-powered stand-ins for the author, the reader, or anyone else.

As always, thanks for dropping by the Literary Mercenary. Your patronage is appreciated, and if you want to help a little more feel free to drop by my

Patreon page, or by clicking the "Shakespeare Gotta Get Paid, Son" button in the upper right hand corner. As always, feel free to follow my latest doings on

Facebook or

Tumblr.

.jpg)